❌ The Two Paths to Self-Control

Why resisting temptation isn’t always about suppressing impulses

We often think of self-control as a battle of willpower that requires us to effortfully inhibit urges that threaten our long-term goals. We might be trying to save money by avoiding tempting purchases, trying to lose weight by skipping dessert, or just trying to resist distractions while working. In all of these cases, all we have to do is nothing. And yet, all of us can recall a time when doing nothing in these situations required intense effort and impulse control.

But perhaps we’ve been overthinking this whole concept of self-control as an effortful exercise. How many of our daily decisions to choose our long-term interests over our short-term impulses really require active impulse suppression?

In a recently published experiment, researchers watched people’s decision-making patterns in real time and quantified how often their decisions showed features of impulse control vs more passive preferences. The results paint a new picture of what our self-control dynamics look like and how we can better utilize them.

🧪 What did the researchers do?

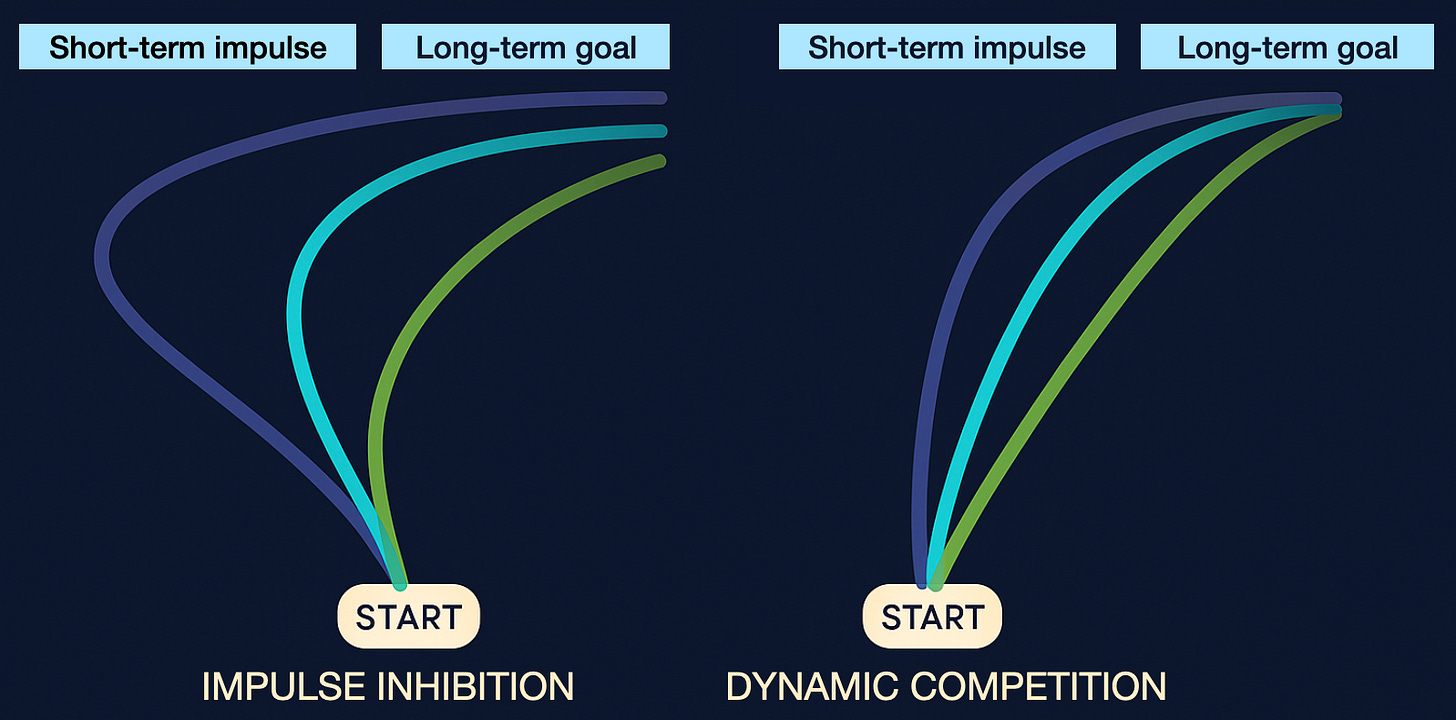

In a new study published in PNAS in November 2025, researchers sought to better understand how self-control actually unfolds in the mind. Do we first feel the pull of temptation and then override it (i.e. impulse inhibition), or do we weigh both options simultaneously until one wins out (i.e. dynamic competition)?

To find out, the research team recorded the mouse movements of 522 participants as they made “intertemporal choices”: classic self-control dilemmas like choosing between $25 today or $40 in six months. Each participant completed up to 210 trials, producing over 100,000 total decisions across the full sample. Some decisions were randomly selected to be paid out with real money, so decisions were realistically incentivized rather than hypothetical.

The researchers analyzed how decisions physically unfolded on the computer screen. When faced with temptation, a participant’s cursor often wavered between the two options. The precise path—whether it veered sharply toward the smaller, sooner reward before correcting back, or gradually drifted toward the delayed, larger reward—offered a window into the hidden mental tug-of-war behind every choice.

By analyzing over 46,000 trajectories where participants chose the larger, later reward, the researchers were able to cluster decision paths into two broad patterns:

Impulse inhibition: The cursor moved sharply toward the tempting, immediate option before being pulled back to the delayed one. This suggested people acted on impulse when the decision options appeared but were able to redirect their energy toward the long-term goal.

Dynamic competition: The cursor moved smoothly and continuously toward the delayed reward, suggesting a more integrated decision process without a clear impulse to suppress.

🔍 What did the research find?

Only 26% of participant decisions showed the hallmark pattern of impulse inhibition. The remaining 74% evolved through dynamic competition, indicating that most acts of self-control don’t involve an internal struggle but rather a patient commitment to a long-term goal over a short-term temptation.

The team then asked whether certain types of people were more likely to show impulse-inhibition patterns. They modeled each participant’s bias toward choosing immediate rewards by calculating how much they discounted future rewards based on how long they would have to wait for them. If curving mouse trajectories truly reflect a need for impulse inhibition, you would expect more impulsive people to use those trajectories more often.

People who were more impulsive were indeed significantly more likely to rely on impulse inhibition when they chose delayed rewards. In contrast, those who were less deterred by delays appeared not to experience strong impulses toward temptations at all. In other words, more impulsive people had to work much harder to commit to long-term goals since they had to effortfully cancel an early urge first.

These patterns weren’t merely explained by decision difficulty. Even during easy choices where the delayed reward was clearly the better option (e.g. $15 today/$32 in a month), both types of trajectories appeared. This suggests that impulse inhibition isn’t just a reaction to hard decisions but rather a personal signature of how some minds resolve temptation.

Impulse-inhibition trajectories were also diverse: some people showed quick, mild impulses that were corrected almost immediately while others showed a stronger detour toward temptation before recovery. Interestingly, the more precisely the researchers captured how participants made their choices, the better they could forecast what people would do in the future.

⭐️ Takeaway tips

#1. Not all self-control feels like struggle

Most successful acts of self-control are not battles of willpower but smooth navigations of competing desires. When decisions feel easier, it may be because your goals are already aligned with your impulses or because you’ve successfully crafted an environment where unwanted temptations are less likely to interfere with your decision-making.

#2. Train habits, not just restraint

There’s a tendency these days for people to work hard in training their sense of control or willpower. People will jump in ice baths, fast for extended periods of time, and wake up at 4am for extra workout time. All of this is commendable and impressive, but it may also occasionally mask easier routes to self-control. We can cultivate habits that make long-term rewards feel more natural. For example, we can set up automatic deposits into our savings accounts, keep only healthy food options in the fridge, and craft workout routines that are easily done at home.

#3. Notice your decision process

Pay attention to how your choices unfold, not just how they end. Do you feel a tug toward temptation before deciding, or does your mind glide calmly toward one option after some deliberation? Recognizing your personal decision patterns will give you more insight into who you are and how you can best manage your self-control skills.

“Temperance is reason’s girdle and passion’s bridle, the strength of the soul, and the foundation of virtue.”

~ Jeremy Taylor

I am addicted to playing Microsoft Spider Solitaire on my phone -- especially while listening to the radio (BBC Radio 4). This in turn incites me to look for more programmes to listen to, to continue playing Spider instead of eg tackling the physical chaos around me.

Spider Solitaire (played with 12 packs of cards) gives a much more satisfying illusion of creating order onscreen, than any such tiring attempt in the three dimensional physical world.

Yet I know the many hours spent jabbing at a tiny phone screen exacerbates muscular strain in my right shoulder & arm, which exacerbates TMJ, which exacerbates eye strain... while my left arm & hand holding the phone go numb.

Years ago I freed myself from Spider Solitaire addiction on a laptop screen, and simply forgot about it for years.

But the ubiquity of smartphone access and the combination with Radio 4 (or a particular podcast) all make quitting this game so much harder.

I've deleted the Solitaire app numerous times -- and as quickly reinstalled it. But recently, something has changed. I find myself listening to "can do" mental chatter, rather than the dispiriting "can't...".

And having most recently deleted the app yesterday? or the day before? -- now do some arm stretching / shoulder rotating / head rolling exercise instead, when I remember the Spider app. And am already amazed how fast the compulsion to play it is disappearing.

It reminds me of how I quit smoking over 10 years ago: by reminding myself, each time that craving assailed me, that I would just have to go through this all over again if I crumbled now.

And the craving was weaker each time it returned -- until it was permanently gone.

It's useful to have an immediate short-term goal as the alternative to addictive behaviour, that supports the longterm goal one aspires to, of freedom from destructive habits.

Did the study assess (control for ) the extent to which the financial rewards were more attractive to participants? Ie. maybe it's not 2 different styles and rather a difference in how attractive the $ was to participants that determined the decision making styles.