🧠 How Open Minds Make Better Thinkers

New research shows that the best critical thinkers are the people who are most aware of their intellectual limits

My most intelligent friends aren’t necessarily the people who are most knowledgable; they’re actually the people who are most aware of what they don’t know.

It’s true that smart people tend to know a lot, but human intelligence reflects more than just encyclopedic knowledge. You need to be able to solve new creative problems, reflect on your own thinking patterns, and recognize your flaws or limits.

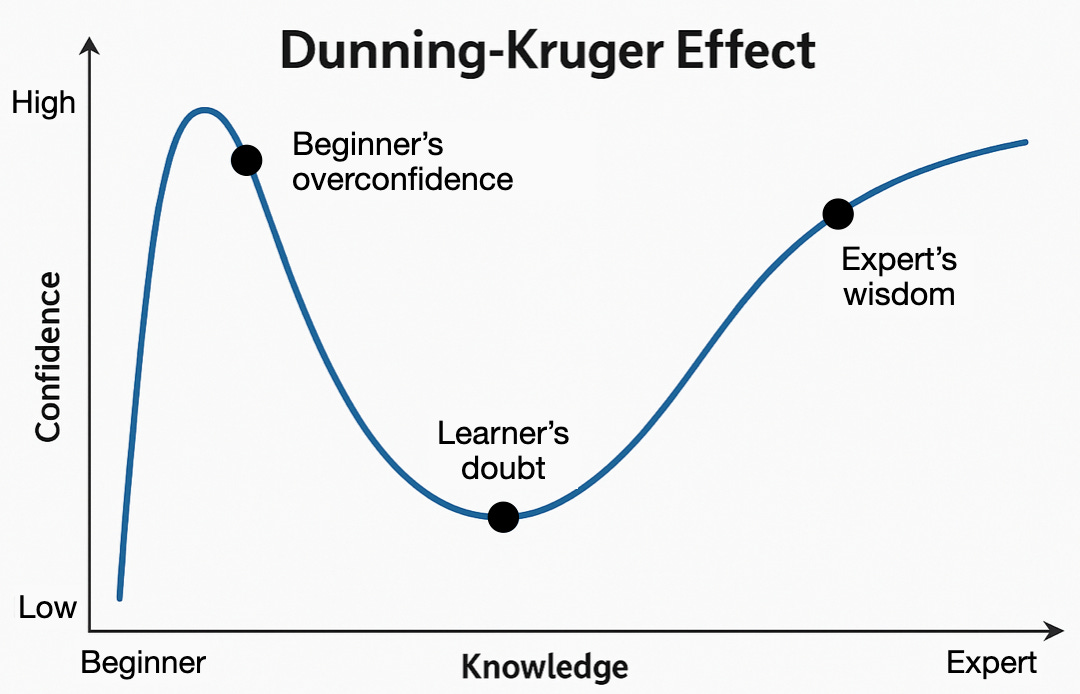

Many of you have probably heard of the Dunning-Kruger effect. This is the idea that beginners in a new discipline tend to be overconfident about their abilities because they’re unaware of the complexities involved in the discipline when they start learning the basics. On the other hand, experts have a good understanding of the nuances so they’re appropriately confident.

We’re all vulnerable to beginner’s overconfidence to some degree but some of us are more aware of our limits than others. We can refer to this ability to recognize our cognitive weaknesses and be open to new evidence as intellectual humility.

New research suggests that intellectual humility may play an important role in how well we reason through complex problems. Humble thinkers are more than just agreeable conversational partners—their humility allows them to think clearly, evaluate evidence accurately, and reflect openly on their own reasoning.

🧪 What did the researchers do?

In a new study published in Personality and Individual Differences (Fabio & Suriano, 2025), researchers investigated whether intellectual humility predicts performance on a range of tasks that require critical reasoning. Tasks included both social and mathematical problem-solving, allowing the researchers to look beyond discipline-specific effects.

The study recruited 115 university students aged 18–32 from several academic programs in Italy. Participants first completed the Comprehensive Intellectual Humility Scale (CIHS)—a 22-item measure assessing openness to revising beliefs, respect for others’ viewpoints, and tolerance of disagreement. Based on their scores, students in the top 10% and bottom 10% were split into high humility and low humility groups.

Next, participants completed a structured test built around five stages of critical thinking established by prior research:

Clarification – defining and understanding the problem

Analysis – breaking down information and identifying what’s relevant

Evaluation – assessing the credibility and consistency of information

Inference – drawing logical conclusions from the evidence

Self-monitoring – reflecting on one’s reasoning and identifying errors

Each participant worked through two sets of problems: social dilemmas in which they had to recommend schools for students, and mathematical problems in which they had to infer hidden numbers via clues. Both types of problem contained relevant as well as misleading information, making critical thinking essential.

🔍 What did the research find?

Across the board, intellectually humble participants performed better on the critical thinking test than those low in humility.

The biggest differences between the groups appeared in the later stages of critical thinking—evaluation, inference, and self-monitoring—where high-humility participants significantly outperformed low-humility peers. These stages involve questioning assumptions, weighing evidence, and reflecting on reasoning, which are the processes most impacted by open vs closed minds.

Performance did not differ between the social and mathematical contexts, so intellectual humility was linked with better critical thinking in general. Regardless of whether a problem was interpersonal or numerical, a sense of humility allowed people to look past their biases and identify the best ways to think through a cognitive challenge.

Critical thinking depends on the ability to pause, reflect, and update beliefs, and intellectual humility gives us the mental space to do that. By quieting ego and curbing overconfidence, humble thinkers can more easily engage deliberate, effortful reasoning that gets around automatic assumptions and avoids jumping to conclusions.

People who can admit what they don’t know are better at analyzing and leveraging what they do know.

⭐️ Takeaway tips

#1. Practice saying “I might be wrong”

Acknowledging uncertainty activates deeper reflection. When you catch yourself defending a belief, pause to ask: What evidence could change my mind? When we’re too confident or wrapped up in a particular way of thinking, it’s very difficult to notice when it’s leading us astray.

#2. Reflect on how you think, not just what you think

After making a decision, take a moment to review how you got there. Did you consider or invite alternative perspectives? Did you look for contradictory evidence? Did you rely on untested assumptions?

#3. Apply humility across domains

Intellectual humility is agnostic about disciplines and topic boundaries. Whether you’re thinking through an artistic challenge, tackling a math problem, or mediating a disagreement between coworkers, the same principle applies: if you’re open to being wrong and changing your mind, you’ll reach stronger conclusions with better outcomes.

“Humility is a virtue all preach, none practise, and yet every body is content to hear.”

~ John Selden