🏃 You Can Run but You Can't Hide

Why avoidance makes things worse

We all have some things we’d rather not think about. But the less we want to think about something, the more it seems to pop into mind.

Trying to avoid or push away thoughts makes things worse over the long term. Thoughts continuously come and go, and trying to battle them is like trying to battle the ocean; you might jump over one wave but the next one is only a few moments away.

As I’ll explain, a more effective alternative to avoidance is acceptance.

By the way, a huge thank you to everyone who has been sharing this newsletter. It helps enormously. If you have friends who might like to read this, please do forward it to them. Reaching more people helps me to make a bigger impact.

🙈 The paradox of thought suppression

In a classic study published in the 80s—cited more than 3000 times—researchers investigated what is now commonly known as the “white bear problem”. They gave a group of participants the following instructions:

“In the next five minutes, please verbalize your thoughts… [but] try not to think of a white bear. Every time you say "white bear" or have "white bear" come to mind, though, please ring the bell on the table before you”

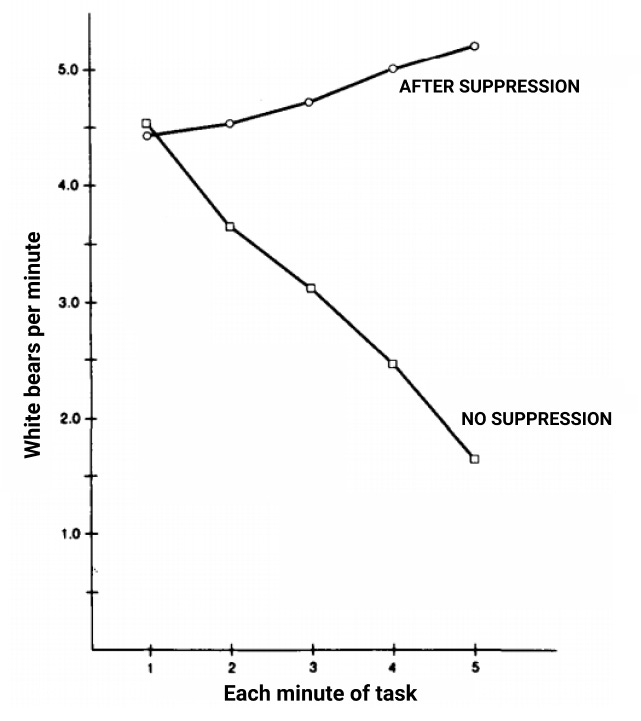

After the five minutes were over, people were free to think of white bears again but were told to keep reporting them with the bell for another five minutes. At this point, the researchers counted how many white bears people thought of and compared those numbers to a group of people who didn’t initially try to suppress the thought.

People were far more likely to think of white bears if they had previously tried to suppress them. In other words, thought suppression paradoxically strengthened an unwanted thought in people’s minds.

As the graph I adapted below shows, people in the suppression group actually thought of more and more white bears over time. In contrast, thoughts of white bears rapidly approached extinction for the non-suppression group.

One theory explaining this strange effect is called “ironic process theory”. It suggests that whenever we try to suppress a thought, our brain does two things. First, it looks for any random thoughts to distract itself with. And second—this is the ironic bit—it regularly checks to make sure we haven’t accidentally started thinking about the thing we’re trying to avoid.

This background monitoring process is essential for detecting when we fail. But in this case, it ironically reminds us of the thought we’re suppressing and ends up reinforcing it. The reinforced thought is then more likely to surface spontaneously in our minds later on.

😰 Do the things that scare you

Annoying thoughts aren’t the only thing we try to avoid. We also run away from activities that make us nervous.

Anxiety is often a sign that you care about something important. So avoiding activities that make you anxious may mean avoiding activities that are highly valuable to you.

Think of public speaking for example. There’s a fear of public failure but there’s also the opportunity to boost your reputation and set yourself up for future success. Avoiding these kinds of activities prevents learning and closes off a chance to excel. It can also make anxiety worse over the long term. The diagrams I made below show what an avoidance cycle typically looks like:

Other smaller daily avoidances are unhealthy too. Procrastinating on a household task or work assignment is likely to make a problem worse over time, as is postponing a visit to the doctor or dentist out of anxiety.

By avoiding problems, you avoid solutions. You can escape cycles of growing anxiety by diving into healthy or productive activities without hesitation. You can then tackle unexpected challenges as they arise.

Similar to going for a swim in a cold pool, it’s best to jump in. No need to prolong the discomfort by crawling in, and certainly no need to avoid the pool altogether and miss out on a moment of joy. Just rip the band-aid off.

One of the best things I ever did to reduce my social anxieties around public speaking was a 10-minute standup comedy set in a pub. My legs were literally shaking on the way up to the stage, but I left the stage feeling on top of the world, and I’ve been far less scared of public speaking ever since. Exposure therapy really works.

🙏 Practicing acceptance

According to the evidence, the most successful strategies for taking control of your thinking involve one basic principle: acceptance. Instead of pushing away uncomfortable thoughts, you need to embrace them.

When you next have an intrusive thought (e.g. something you’re worried about or an annoying song stuck in your head), don’t push it away. Just let go and observe what your mind does with it.

Don’t fight negative emotions like sadness, anxiety, or anger. Negative emotions are important signals so pay close attention to them, but they also tend to stick around longer than they’re useful. So when there’s no longer a problem to solve, acknowledge emotional sensations around your body without needing to judge or interpret what those sensations mean. Just like the white bears, negative emotions fade away sooner with acceptance than with avoidance.

If there’s an important task you’ve been putting off, make time for it now. Procrastination is the enemy of progress, and boring or difficult tasks are rarely as boring or difficult as you imagined they would be.

💡 A final quote

“Avoiding danger is no safer in the long run than outright exposure. The fearful are caught as often as the bold.”

~ Helen Keller

❤️ If you enjoyed this, please share it. If you’re new here, sign up below or visit erman.substack.com

📬 I love to hear from readers. Reach out any time with comments or questions.

Until next time,

Erman Misirlisoy, PhD

Like The Brainlift on Facebook

Follow me on Twitter

Follow me on Instagram

Follow me on Medium

Connect on Linkedin