There’s a strange lure to thoughts like “what if…?” and “if only…”. When you skip a party to stay home with a movie, it’s natural to think “what if I’m missing out on the fun?”. And when you choose the party, you might think “wow it’s noisy here—if only I’d stayed home with a movie”.

These what-if scenarios are referred to as “counterfactuals”, and most of us are obsessed with them. Research is now starting to show just how seductive counterfactuals are and how much they can hurt you.

😓 The pains of counterfactual curiosity

Earlier this year, a group of researchers from the UK and Japan published a study testing how much people would be tempted by the thought of what could have been.

Their experiment featured a game called the Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). In this game, people watch a balloon and decide whether or not to hit a pump to inflate it. Every time they hit the pump, they slightly inflate the balloon and gain points that they can convert to cash after the experiment. The problem is they don’t know exactly when the balloon will burst, and the bursting point is selected at random between 1 and 12 pumps. If the balloon bursts, they lose all the points they accumulated for that balloon, so the aim of the game is to bank your points before the balloon explodes.

Since the bursting point is chosen at random, the BART is mostly a game of chance. Every time you decide to inflate the balloon and gain a few extra points, you’re gambling on the fact that it won’t burst yet. But the researchers weren’t particularly interested in how many points each person gained. They were more interested in measuring how much people wanted to know the bursting point on a balloon after they banked points.

This is what they called “counterfactual curiosity”. It won’t help you to find out where a balloon would have burst if you kept on inflating. But how curious would you be to find out?

The researchers ran this experiment five times with a total of 150 people. When there was no cost associated with finding out a balloon’s bursting point, people asked for it 67% of the time after banking points. That’s a whole lot of curiosity for something that doesn’t really matter.

But the strangest part is that people were tempted by their curiosity even when there was a cost to checking a balloon’s bursting point. When they had to pay with time penalties or physical effort (i.e. rapid key presses), they checked around 50% of the time. And when they had to give up cash (i.e. points), they still checked 18% of the time.

The researchers also measured the emotional consequences of learning about these counterfactuals. Even if there’s no immediate cost to thinking about a counterfactual, the outcome might make you feel bad, which is ultimately an emotional cost.

Across the experiments, people generally felt emotionally worse when they found out where the balloon would have popped. And yet, their curiosity consistently got the better of them.

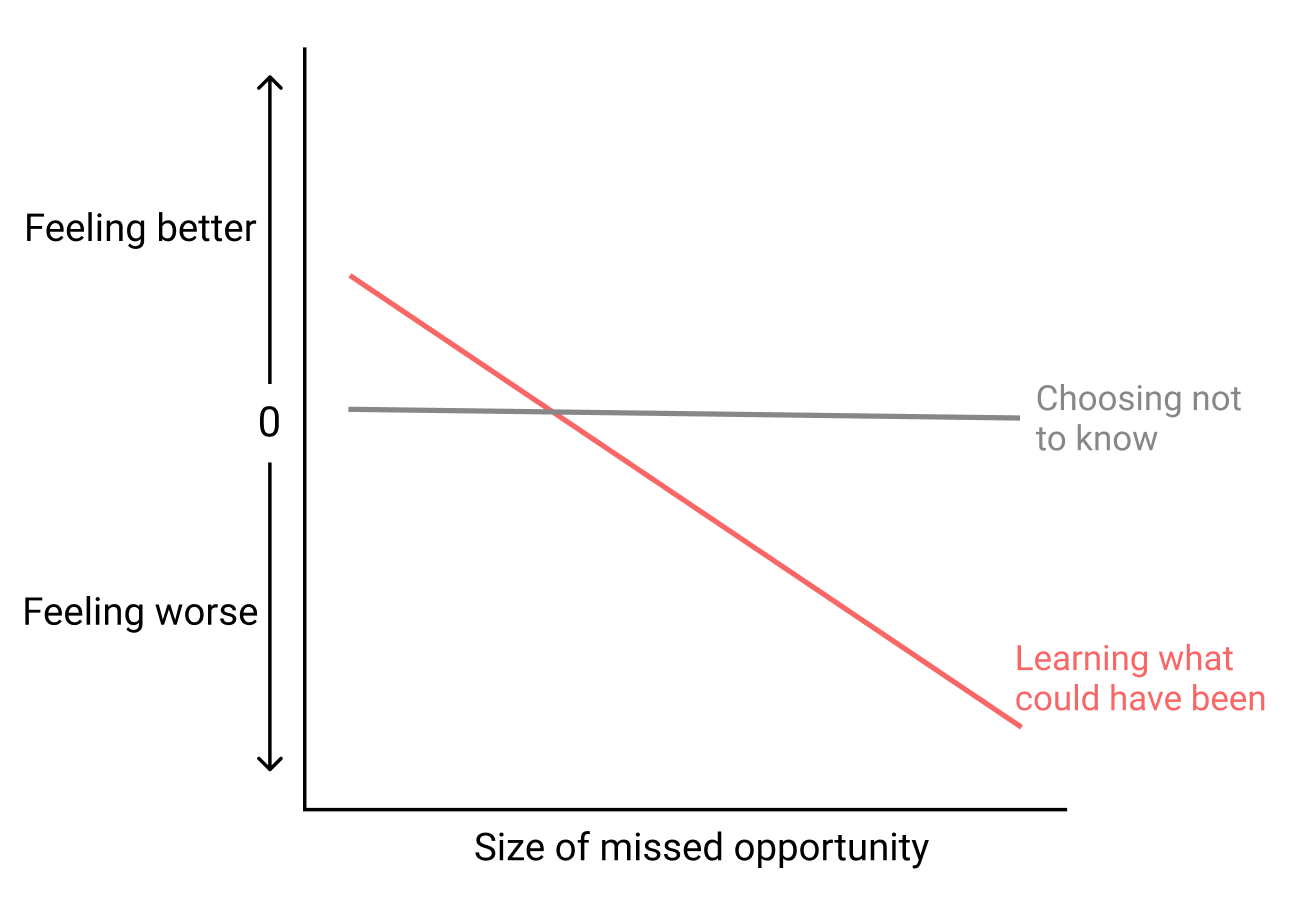

Here’s a schematic version of one of the graphs from the paper showing that emotional harm was more extreme when people found out they could have inflated the balloon much further than when they stopped. The bigger the missed opportunity to earn money, the worse people felt.

Counterfactual thinking might occasionally be advantageous. If thinking about an alternative possibility reveals that you’re currently better off, you’ll feel happier. You can see this at the start of the graph above where people feel slightly better if they find out they didn’t miss out on much. But in the grander scheme of counterfactuals, that’s relatively rare. Counterfactual thinking commonly goes wrong in two ways:

The negativity bias (you can learn more about this bias in one of my previous newsletters): When counterfactual thinking offers no objective information, your mind gets to run wild, and you can end up believing you’ve missed out on something amazing when you haven’t. This is because our minds gravitate toward negative emotional information.

Pointless curiosity: Even when you can actually learn from counterfactual thinking, it may not serve any purpose or advantage. You might find out that you really are worse off, but what’s the point? You end up risking your emotional stability with nothing to gain.

In the real world, these patterns play out all the time. We can’t help but wonder what could have been, and our imaginations leave us in bad shape.

⭐️ Takeaway tips

Don’t worry about what you can’t control: A centerpiece of Stoic philosophy is that there’s no point in worrying about things you can’t change. If you’re anything like me, you’re not very good at taking this advice, but practice helps.

Avoid pointless curiosity: Curiosity is incredibly important for learning and self-improvement but sometimes it’s misguided. Before wasting mental energy on a question like “what if?”, consider how much value it’s adding to your life and the potential damage it could do if it’s bad news.

Enjoy what you have: Counterfactual thinking focuses your mind on what could have been rather than where you actually are. This often means you fail to appreciate many of the great things in your life, which isn’t good for mental health. There’s nothing wrong with being ambitious and wanting to improve, but don’t lose track of what you’ve already gained.

💡 A final quote

“No person has the power to have everything they want, but it is in their power not to want what they don’t have, and to cheerfully put to good use what they do have.”

~ Seneca

❤️ If you enjoyed this, please share it with a few friends. If you’re new here, sign up below or visit erman.substack.com

📬 I love to hear from readers. Reach out any time with comments or questions.

👋 Until next time,

Erman Misirlisoy, PhD