Pictures can’t ever tell a complete story, but they communicate a particular moment in space and time that’s worth reflecting on. Those moments often feature human beings, because we value the exercise of reading another person’s mind and relating to what they’re feeling.

Even the best artists and photographers can’t reproduce the full intensity of a lived experience though. They’ll often creatively enhance particular feelings or expressions via their style and framing, but seeing someone in a picture is rarely as potent as seeing that person in the flesh.

Common sense would say that this isn’t surprising: a two-dimensional image can never be as impactful as the multi-sensory experience of truly living in the moment. But there’s more to the story than just sensory richness. Even the most perfectly detailed image of a person introduces a layer of abstraction relative to a viewer. And the deeper that abstraction goes, the less human we see the person.

Since Medusa’s reflection was weaker than her direct gaze, researchers are calling this the Medusa effect.

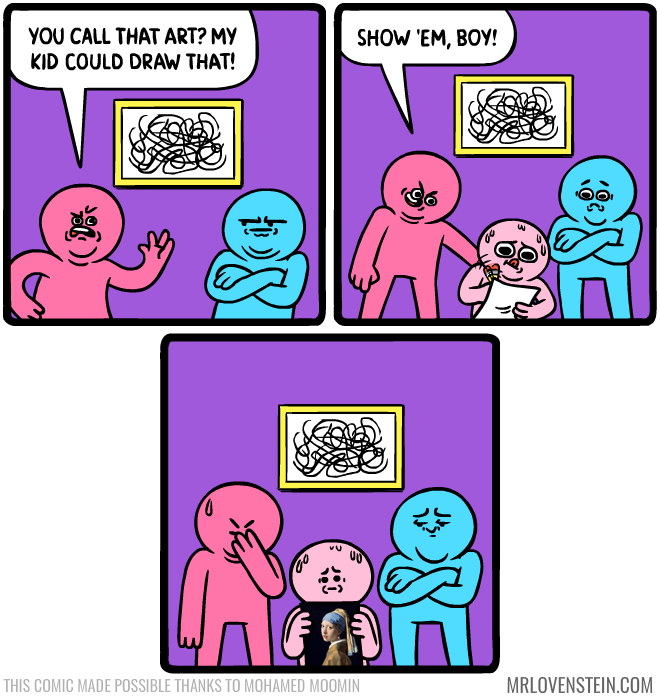

🖼 The person in the picture of a picture

In a 2021 study, researchers at the University of British Columbia and University of York showed 320 people a set of 30 photographs. Each photograph contained two people within it: one living in the photo environment itself (let’s call them “Player 1”) and then another person in a picture within the photo environment (let’s call them “Player 2”). For example, a photo might feature a person looking at a portrait of another person, or perhaps a person having a video call with someone else.

For each photo, people had to rate which of the two people—Player 1 or Player 2—felt the most real, had the deepest feelings and experiences, or seemed the most morally competent and able to control their actions (i.e. had the most agency).

84% of participants rated Player 1 as more real than Player 2, and around 70% of people believed Player 1 had deeper experiences and more agency. In other words, the way we interpret a person’s mind is impacted by their level of abstraction in relation to ourselves. In a direct interaction with another person, we see them as human just like we are: they have rich emotions and intentions that guide their lives. But when we see a person in a picture, we perceive their minds as less vibrant. And when we see a person in a picture of a picture, their minds appear even duller.

The researchers ran the same experiment again but avoided asking people how they interpreted pictures, since people’s reports are often misleading. So they instead tracked where people’s eyes were looking every time a photo appeared on-screen. Eye movements reveal where a person’s attention is focused and therefore hint at what they’re thinking or processing in each moment.

When photos first appeared, people’s eyes were more drawn to Player 2 as they tried to work out what was going on in the scene. But within a couple of eye movements, they showed a prolonged preference for focusing on Player 1. This deeper processing of Player 1 left people with a stronger sense of empathy for that person’s mental states.

These effects persisted even when the researchers used the same person in the Player 1 and Player 2 images and precisely matched their relative sizes within each photograph. Regardless of the size or quality of each picture, there was a clear bias towards connecting less deeply with the humanity of people who were more removed from the viewer.

This disconnection was more than just a perception; it impacted real behavior too. In a final experiment, people were paired up with either Player 1 or Player 2 from the photos and were asked how much of a $10 gift they wanted to share with that person. On average, people offered Player 1 a very generous $5.48 while offering Player 2 only $4.42.

The way we interpret a person’s mind directly affects how we treat them, and the way we interpret their mind is affected by the perspective from which we view them. The more removed we feel from the person we are looking at, the less we appreciate and respect their basic human experiences.

⭐️ Takeaway tips

Another reason to meet in person: People on a screen are harder to relate to than people who are standing next to us. We have an impoverished perception of their minds. In the experiment above, people were less financially cooperative with people on screens, but the effects are likely to be more subtle in real-life scenarios such as video-chatting with colleagues. Perhaps we’re more likely to assume a bad intention when people behave ambiguously on a screen rather than in person, or maybe we’re a little lazier in offering them help or guidance. It’s important to be aware of these kinds of social biases so that they don’t impact our behavior in a way we might later regret.

Counter social biases: We view more abstracted people as having less agency and less rich experiences than people we view directly. Think of where this bias might impact your own life. For example, do you ever look someone up online before meeting them in person for the first time? If you judge people via a picture before meeting them, it might lead you astray and create negative expectations that affect your interaction later on.

Give generously: It’s frequently true that the people who most need our help are people we only ever experience through some kind of image or indirect communication. Whether we see people fleeing war-torn countries on the news or poverty-stricken people in charity ads, they’re layers of abstraction removed from us. People deserve help regardless of how distant or dissimilar they seem, so be conscious of where exactly you spend your altruistic energy and why.

💡 A final quote

“Photography, if practiced with high seriousness, is a contest between a photographer and the presumptions of approximate and habitual seeing.”

~ John Szarkowski

❤️ If you enjoyed this, please share it with a few friends. If you’re new here, sign up below or visit erman.substack.com

📬 I love to hear from readers. Leave a comment on this post or feel free to email me your questions.

👋 Until next time,

Erman Misirlisoy, PhD